The Gist:

Climate change is often brought up as this world-ending, man-made problem. In the same vein, people often point to humanity taking proper action to protect the environment and change our ways as a solution. Going forward, let’s assume two things. First, the economic systems of extraction, production, and transportation that we have in place are contributing to climate change (or if you don’t want to ascribe causality to it because you don’t trust the research, we can rephrase this assumption as “there is a positive correlation between man-made industrial systems and an increase in global temperatures”). Second, these systems can be disrupted by climate based events and patterns (ie weather patterns in various regions change which in turn affects what land is arable across the globe, extreme weather disrupts human movement patterns, and climate distasters have the capacity to pose dangers to or destroy existing infrastructure and resources). In other words, the climate and man-made systems are inherently linked. As members of society who participate in and rely on these man-made systems, we are also the ones who face the effects of damage to these systems. Though the driving force for this damage is ecological, the impact it will have on the average person is an issue of economics.

Thesis: If things continue as they are, the economic systems we have in place that are contributing to climate change will be forcibly scaled back by the effects of climate change, leaving the average person to face major economic impacts of climate change rather than ecological ones.

Basic Macro-Economic Theory

Before we can talk about why the problem is an economics issue, we need to be on the same page about three basic economic concepts.

- What is Economics the study of?

- What are supply and demand?

- How do we view these on a larger scale?

What is Economics the Study of?

When I was first asked “What is Economics the Study of?” in my high school economics class, I wrote the same thing most people in my class had: “Money.” The cultural notion of “economics” puts money at the center of “economic” discussions, so it seemed inevitable that “economics” was “the study of money”. This is not true.

Economics is the study of scarcity.

A lot of people would read, “the impact [climate change] will have on the average person is an issue of economics,” and think “this is an issue of cash. Dollars and cents.” But that’s not what the true economic impact of climate change looks like. Dollars and cents are merely a standardized way to store value and track the allocation of scarce goods and services. Economics can be studied in barter systems on a elementary school playground or prison yards, places often devoid of cash.

Going forward, it is paramount to think of the economic impacts of climate change as an issue of resources and scarcity. Don’t think empty wallets, think empty grocery store shelves. It’s not just an issue of high rents. It’s an issue of housing shortages as sea level rise damages coastal dwellings.

Without thinking about money, we must consider what it would look like to live in a world with less stuff (and potentially fewer people). What does the world look like when food doesn’t grow in some parts of the world anymore?

What are Supply and Demand?

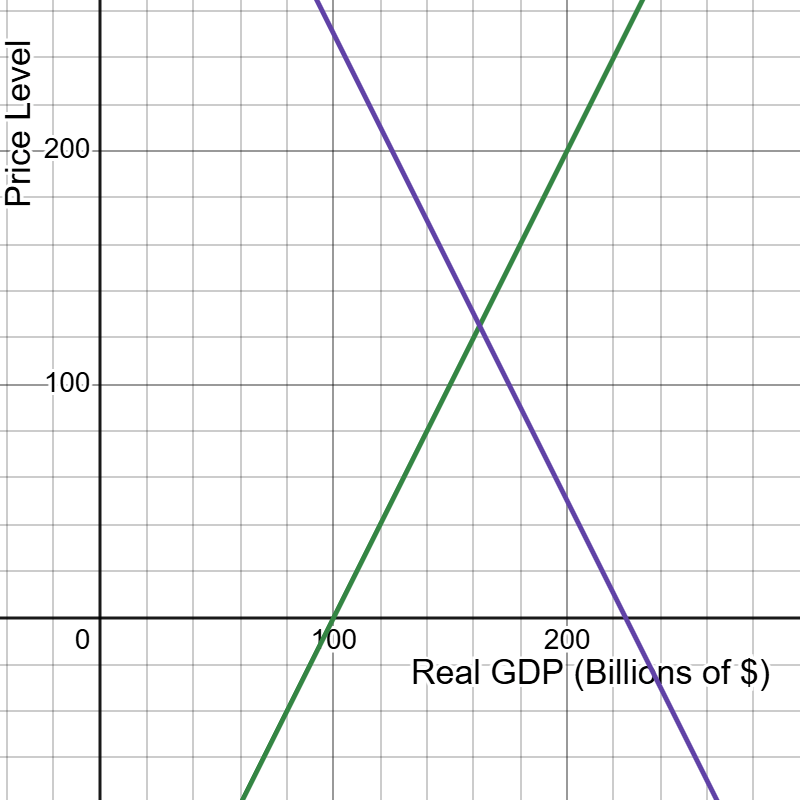

In economics, two fundamental principles are those of supply and demand. Supply is the amount of a particular good or service that is available. Demand is people’s willingness to acquire that good or service. These can shift based on a number of factors, but it is important to note price is not one of them. Below is a graph to explain the difference between “Supply and Demand” and “Quantity Supplied and Quantity Demanded”.

The green line is the Supply curve. The blue line is the Demand curve. Each is a function of quantity defined by price. The points that are defined by these functions are the Quantity Supplied and the Quantity Demanded, respectively. The Quantity Supplied and Quantity Demanded are changed by changes to the price. In other words, if the price goes up, the Quantity Supplied goes up (because the Supply curve is positively sloped) and the Quantity Demanded goes down (because the Demand curve is negatively sloped).

The point where the two intersect is the equilibrium point where the Quantity Supplied is equal to the Quantity Demanded. Naturally, a market for any good, without interference, should end up at the equilibrium price and equilibrium quantities. This tracks because at this point, no supplier is creating more than they can sell, and no consumer is demanding more than is available. If you were to exist at a price above this point, then sellers would have excess to sell and nobody to purchase it (Quantity Demanded is lower than the Quantity Supplied). If you were to exist at a price below this point, then there would be buyers who were willing to pay more and not receiving a product and suppliers who are missing out on potential gains by selling more product (Quantity Supplied is lower than the Quantity Demanded).

Now, we have established what Quantity Supplied and Quantity Demanded are and how those are both affected by changes in price. So, what did I mean when I said Supply and Demand “can shift based on a number of factors”?

Supply and Demand do NOT change with changes in price. They are the functions that define the lines we see in the graph above, and as we see in the graph below changes to Supply or Demand change the relationship between price and quantity. Supply can shift for reasons such as changes to input costs, development of more productive technology, increases/decreases in the amount of producers, etc… Demand can shift for reasons such as changes to consumer income, shifts in preferences of consumers, prices of related goods (ie if hotdogs become more expensive, Demand for hotdog buns would decrease), changes to population, etc…

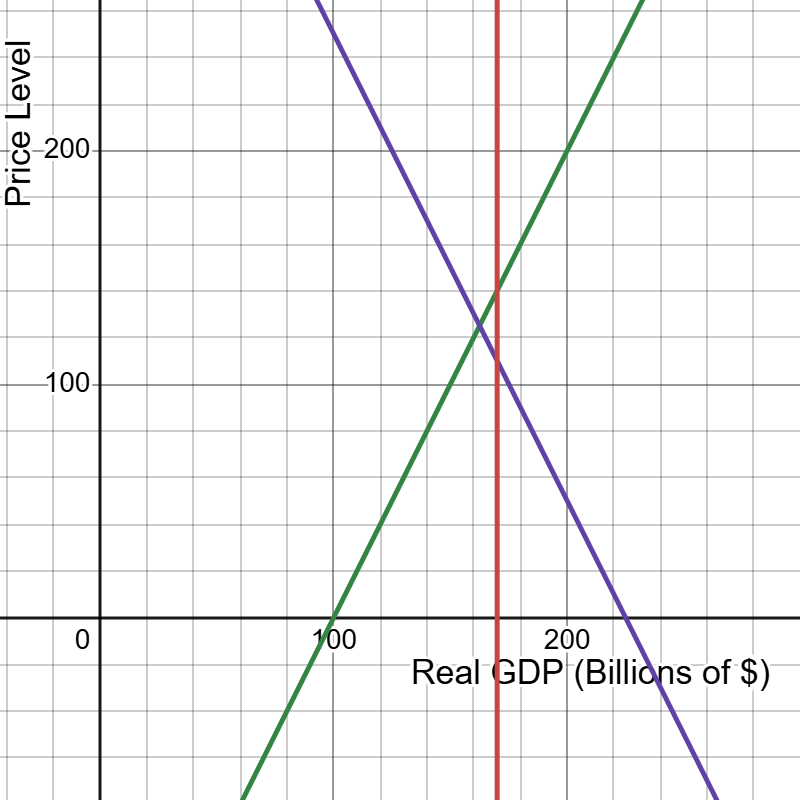

Below, we see an example of a leftward (or negative) shift in supply.

In this image, the blue line is still Demand, the green line is the original Supply, and the red line is the new Supply. This shift could be caused for any number of the reasons mentioned above. Perhaps this graph represents a market for apples, and the cost of fertilizer went up. Perhaps this graph represents a market for cars and a fire at manufacturing factory led to the factory’s closure. Regardless, the supply has shifted negatively. The new equilibrium price is higher, and both the equilibrium Quantity Supplied and Quantity Demanded (see the intersection of the blue and red line) are lower. In other words, there has been a negative economic impact on this market due to the sudden decrease in Supply.

This phenomena where supply shifts negatively leading to an increase in equilibrium prices and decreases in equilibrium quantity is known as Supply Shock. It’s one of the worst types of shifts you can see in any market because of this dual negative effect. Imagine a scenario where not only are the shelves empty at the grocery store, but prices are higher. You may have seen this recently in the market for eggs when egg prices soared, but the store had fewer eggs on the shelves due to an outbreak of bird flu. That’s Supply Shock.

What is Aggregate Supply?

Now, we have defined Supply and Demand for a single market. This could be the market for eggs or the market for hammers. Regardless, the examples above cover a singular market for a singular good or service. But what about on the macroeconomic scale? How can we see the effects of large-scale changes on the economy as a whole. For this, we introduce two new concepts: Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand.

These are the total supply for goods and services in an entire economy (Aggregate Supply) and the total demand for those goods and services (Aggregate Demand). The axes on which they are defined are different than just “Quantity” and “Price”. Instead, these are defined by the Real GDP (or the total output) of an economy, and the Price Level (which is the average price of goods and services in the economy).

Side note: To conceptualize these better, we can relate Real GDP and Price Level to Quantity and Price from before, adding in some abstractions along the way. So if you’re unfamiliar with what GDP measures and how “Real GDP” and “Nominal GDP differ, when you see “Real GDP” in this blog, feel free to think “Total Quantity of Stuff” in the economy. If you see Price Level, feel free to think “Average Prices of Stuff” in the economy. Another key thing to help understand Price Level is understanding that inflation increases Price Level. If we have inflation, the Price Level increases. If we have deflation, the Price Level goes down.

In it’s simplest form, we have now moved from a graph that looks like the ones presented above, to the same general graph with a new X- and Y-axis, such as the graph below.

Looks familiar, right?

There is one more thing to consider though. In economics, there is a concept of both Long Run Aggregate Supply and Short Run Aggregate Supply. In the graph above, we see the Short Run Aggregate Supply (SRAS) presented by the green line. It is variable and shifts to accomodate short term changes. On the other hand, we have Long Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) which is not yet depicted. LRAS is an economy’s maximum sustainable output given its labor force and capital (“capital” meaning tools, equipment, resources, etc…, basically everything except labor that goes into making stuff). In other words, an economy has certain amounts of people and equipment that can be used to provide goods and services. The maximum possible Real GDP that can be created in this economy without causing issues such as excessive inflation is the LRAS. Because this is a single value that does not change with Price Level, we represent LRAS with a verticle line (see below).

In the graph above, the Long Run Aggregate Supply is presented with a verticle red line, while the Short Run Aggregate Supply is denoted with the green line and Aggregate Demand is denoted with the blue line.

SRAS and LRAS can be affected by similar or different factors. If input costs for the production of goods drops down, you might see SRAS increase while LRAS does not. For example, if the price of oil goes down, then all industries that are dependent on it to make their products will be able to create more at a lower cost, so SRAS increases (a move to the right). That said, the price of the input can fluctuate and there are no more capital, labor, nor technological changes in the economy, so LRAS does not change. Alternatively, the development of new engines that burn oil more efficiently leads to both an increase in SRAS and LRAS because these machines have fundamentally changed the production capabilities of the economy when working with the same amount of oil. Thus in the long run and short run, production has increased.

As we look at the macroeconomic effects of climate change, we will be considering both SRAS and LRAS, along with the previously defined phenomena of Supply Shock.

Climate Change and the Economy

Climate change is inherently an environmental problem. As average global temperatures warm (man-made or not), we will continue to see adverse effects on our planet such as increased drought, more extreme natural distasters, sea level rise, etc… Unchecked, these changes will negatively impact both the Long Run and Short Run Aggregate Supply. As mentioned in the “What are Supply and Demand?” section, these negative shifts of LRAS and SRAS will lead to a higher Price Level and a lower Real GDP. In other words, society letting climate change get worse means “higher prices and less stuff” overall. The worst of both worlds.

It is scary to think that extreme weather events are more common now. That people are dying from and will continue to die from things like blizzards, wild fires, wet-bulb conditions, etc… that are only getting worse as the years continue. It is scary to think that climate migration by displaced people has been on the rise and continues to rise as the number of inhabitable regions of the planet decreases. As people lose their homes to an increasing number of distasters. As the Earth becomes less friendly to those who inhabit it.

But, given our first assumption that the systems humanity has in place are contributing to climate change, it is also unlikely that any particular person will be killed by a natural disaster. The systems that allow for us to have our current LRAS and SRAS contribute to climate change, but they are also the systems that will weaken, leading to decreases in the LRAS and SRAS of our economy. Ultimately, we will reach a point where we are doing less damage to the climate as LRAS and SRAS are scaled back. The world is fighting back, and it can only end in stalemate.

Does this mean people will die? Yes. People are already dying from climate change. To ignore this fact is to boast one’s morbidly unempathetic ignorance. But at the end of the day, even those who do not die directly from a climate related incident will face the effects of climate change as they see higher prices and empty shelves everywhere they go. They will inevitably feel pain brought about by ruptures to our economic systems that were caused by those same systems. As if it wasn’t hard enough to get by in the modern age and people all over the world weren’t struggling with their localized cost-of-living issues, the situtation will only get worse. And as always, the poorest people will face the pain of these systemic and environmental failures first (though again, everybody will have to face it eventually if something is not done).

The average person may not die in the cold of extreme sub-zero temperatures, but they might go to bed hungry some nights. And it is a long road until enough people face that reality that we may collective say “it’s time to do something about this”. We are imperfect, myopic beings after all, and we tend to live by an “if it ain’t broke” mentality, regardless of whether or not we know it WILL break. Assuming the people who have the greatest influence to make the necessary changes now are also those who will face these pains last, it follows that these people are disincentivized from making the necessary changes to our existing systems until most of us have already been negatively impacted by their failings. As the environment is damaged, our capacity to have the same level of goods and services we currently provide will decrease, and society will inevitably have “less stuff”. At the end of the day, the average person will be faced with a problem of scarcity.

So What Do We Do?

Do we elect poorer politicians? The type who have faced and will face the effects of climate change. Do we elect younger politicians? The type who will actually have to live with the long-term consequences of their policy decisions as it relates to the climate and the economy. Do we stop driving cars, using energy intensive AI, and cut back on red meat consumption?

I don’t know. This post wasn’t about that.

This post was meant to argue how and why I view the issue of climate change as an economic one. To illustrate to people how they can expect to be impacted by it, especially if they aren’t worried about the environmental impacts. I’m not saying we shouldn’t do all of those things. We probably should if we can (though, understandably, not everybody can). I just can’t promise it will make enough of a difference given how reliant we are on other contributors to climate change. At the end of the day, we all participate in the larger economic system that has been perpetuating global temperature rise for generations, and that’s a very difficult thing to move away from.

But it’s a huge problem that requires collective action, and collective action is an incredibly hard thing to manage. What do we do if we can’t take on the system alone and we don’t have the critical mass of support to fix the issue? What am I doing about it?

Why I’m Making an Ecovillage

My goal is simple: Become less dependent on the existing systems I believe are going to fail.

If systems like financial lending, reliable supply chains, social security, etc… are going to face ruptures that hurt me and the people I care about, then I should find a way to no longer rely on these systems. A way to be as self-sufficient as possible.

To create a place that is relatively self-sufficient, I needed to consider what that meant. Homesteading is a start, sure, but that’s not living a life. That’s surviving. That’s scraping by and replacing damaged systems with an isolated living situation. I wanted more than that, and more importantly, I didn’t want to leave all the people I love behind to face the collapse of societal and economic systems alone. Thus was born, the ecovillage. A sustainable community consisting of my friends and family (who wished to live there or needed to after unfortunate circumstances) that worked to mix the comforts and joys of being part of a society with the security of being self-reliant.

It’s a small start, and it doesn’t save the world or stop climate change, but it helps the people in my life stop being reliant on our precarious systems while operating on a feasible scale. My dream is to build a community where those I care about are safe from the failure of our flawed, climate-change-inducing systems. A safe-haven where we can remove ourself from these systems as much as possible and contribute less to climate disaster. I can’t say it’s for everybody, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t still try our best to mitigate the effects of climate change (if not for us, then for those less fortunate than us who will see greater impacts sooner), but it’s what I can do for those around me. And if the world falls apart around us, I’ll know I did my best, and that’s all any of us can ask for.

Leave a comment