The Gist:

No, we don’t have free will, but we should live as if we do.

Defining Free Will

As we are making an argument in regards to whether or not people have free will, it is important to define what we mean by “free will”.

For the remainder of this article, we should think of “free will” as the capacity of an individual to be the source of the actions they take or decisions they make, and in doing so, change a course of events.

Some people may interpret a “lack of free will” by this definition to mean that everything is predetermined. This is wrong. That said, if everything is predetermined, under this definition there is no free will.

The Argument

Case 1: There exists an omniscient deity

Assumptions:

- The deity knows or has the power to know everything

- To be “omniscient” means to know everything that will happen in the future with 100% accuracy

Argument

If an entity can know everything, then they know the future. Thus everything is predetermined and all our actions are deterministic. We, in this case, are unable to make decisions that differ from the deterministic path of events known by the omniscient deity. By our definition of free will, we are unable to change any course of events. Thus, we do not have free will.

Case 2: There does not exist an omniscient deity

Assumptions:

- We cannot control individual molecules

- Cells are made of molecules

- Our brains are made of cells and molecules

- The activity in our nervous system is born from the interactions between cells and molecules in nervous system

- Our decisions and actions originate from our nervous system’s activity

we do not control Our Actions

Following the assumptions we have made above, we can think about our actions as an inductive case. First we would like to use some of the assumptions to establish a simpler understanding of how the brain works. Since cells are just a collection of molecules, we can consider the interactions between cells and molecules in the nervous system as interactions between molecules. Now, looking at the action cascade, we consider what happens when we perform an action.

The Action Cascade: We perform an action. This action is caused by activity in our nervous system. This activity in our nervous system is the product of molecules interacting.

In the reverse order, we can see it as a set of interactions that manifest as us performing an action. Molecules interact and produce activity in our nervous systems. This activity manifests as an action we perform (which is another set of cells/molecules/atoms interacting) or our brain making decisions.

As a consequence of this action cascade, we are not in the source of our actions or decisions. Our actions/decisions originate from interactions between molecules.

Side note: This is not saying that everything is deterministic since we have no control of our actions. Assuming the interactions between molecules are not deterministic, then the outcome of the action cascade is not deterministic, and the world we live in is not deterministic. That said, regardless of whether or not things are or are not deterministic, we do not control the underlying processes that manifest from our perspective as actions and decisions.

Conway’s Game of Life

I believe a better way to understand the above argument is through a simplified example of the action cascade. For this, I present Conway’s Game of Life, a zero-player game.

The Game Construction

The game is a simulation played out with a grid of “cells” (spaces on the grid) that can take on a binary value of “alive” or “dead”. Theoretically, the play-space of the game (ie the grid) is infinite in all directions. Imagine an infinitely large excel spreadsheet where cells either take on a shaded or unshaded color in order to indicate whether or not they are in the “alive” or “dead” states.

Prior to the game, the board is presented with an initial state. In this initial state, some cells are set as “alive” while the others are left “dead”. From this initial state, the simulation goes round-by-round, calculating the liveliness of each cell on the grid before moving to the next generation. To determine whether or not a cell is alive or dead from one generation to the next, the game follows 4 simple rules:

- Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies, as if by underpopulation.

- Any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on to the next generation.

- Any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies, as if by overpopulation.

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell, as if by reproduction.

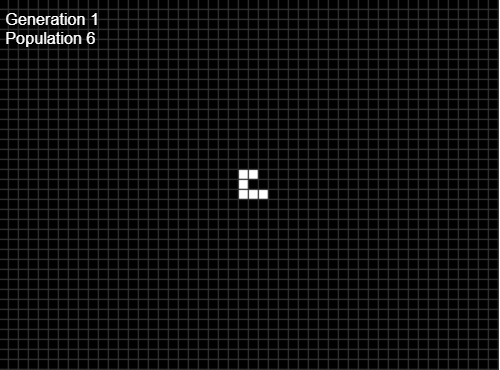

In other words, a cell is determined as alive or dead in the next generation based on the number of alive cells surrounding it in the current generation. An example of these generational steps can be seen here where a game that starts with a population of 5 changes shape and grows to 6 living cells:

Through this simple place space of binary cells and set of four very simple, interesting and complex patterns are able to emerge. An example can be seen in the following GIF:

This GIF shows a certain pattern called a “Glider Gun”. The repeating pattern of a small collection of cells going off to the bottom right infinitely are called “gliders”, and the oscillating pattern of cells above creates these gliders, hence the name “Glider Gun”. There are many more patterns that have been discovered from different initial starting positions in the game, but the point is, even simple rules dictating the binary state of cells on a 2-dimensional grid can create elaborate patterns that develop and exceed the initial state of the game. Regardless of interactions from a player (hence the categorization as a zero-player game), the world in Conway’s Game of Life develops all on its own.

Conway’s Game As An Allegory

Relating our world to this microcosm, we can consider the generational rounds from one state to the next as our experience of the passage of time. The cells are atoms/sub-atomic particles. The rules are the laws of physics and quantum mechanics that dictate interactions between various atoms and sub-atomic particles. The grid is all of 3D space.

Unlike Conway’s Game of life, interactions on the quantum scale are not so deterministic. Nevertheless, these smaller interactions develop into larger patterns. Just like in Conway’s Game of Life, we have structures larger than their atomic parts, and these can interact to create even larger structures. A single cell in the human body is just a more complicated example of this same principle. Where Conway’s Game of Life may have Glider Guns, our cell membranes have Ligand-gated ion channels.

Our universe is simply a very large and complex version of Conway’s Game of Life. The rules follow probability distributions rather than deterministic outcomes (consider the phenomena of quantum tunneling), but the conclusion is the same. Smaller cells, given some initial state and set of rules, form a complex world of larger structures.

You, me, and everybody we know, cannot dictate these rules nor change the initial state of the game. Much like a pattern in Conway’s Game of Life, we are automota, built by smaller cells folowing rules, and our universe is a zero-player game. Our nervous systems are just smaller processes of interacting molecules that are following the rules that set them in motion. We do not get to determine what happens in these processes. Like gliders going out across an endless grid, we are simply moving through our world as its rules dictate we should.

Living With This Knowledge

Not having free will can be a scary prospect. It has a lot of implications. For example, if we don’t have free will, what does that say about personal responsibility? Accountability for one’s actions keeps the world in order and makes it a better place to live, and a lack of accountability makes people act in ways that often hurt others and/or themselves.

How can I be held accountable for my actions if I am not the source of them? Is it reasonable to punish someone for a heinous crime if they didn’t have free will, and thus did not have the agency to stop themselves from doing the crime? Was the crime not bound to happen anyways? What’s to stop me, now that I know I have no free will, from doing something insane and reckless? I was going to do it anyways, no? I can’t be held responsible for the outcome because I was not the source of the action in the first place.

Though no amount of arguing will answer these questions nor give us the free will we never had, they are, nonetheless, worth our consideration. That said, the solution to all of them is simple.

We, collectively, have to continue living as if we do have free will. We have to consider ourselves as free agents, making decisions on our own accord, and being accountable for the outcomes our actions lead to.

Regardless of the reality of the situation, as long as everybody continues to live as if we do have free will, questions of accountability become trackable, managable, and fixable when issues occur as the result of one’s actions.

Conclusion

This is not the only argument for why we do not have free will. There are numerous research papers and logical arguments that also point to the same conclusion. This is just the argument that made the most sense to me and helped me accept our lack of free will.

To me, the Conway’s Game of Life allegory did more than show me how complexity is derived from simplicity and how we are just results of that complexity in our own world. It tied together my existential dread from learning about the mechanisms cell biology in high school with the larger philosophical issue of our lack of free will. Beyond a logical understanding of the arguments that had been presented to me, the action cascade argument and Conway’s Game gave me a means to come to terms the arguments I had heard.

Nevertheless, everyday, I live as if I have free will. I know I do not, but I continue to act as if I do. The choices I make still affect me and the those around me. If I do something rude, I apologize. If I make a mistake, I acknowledge it. If I have to decide between A and B, I weigh the pros and cons. Regardless of the fact that my actions and choices are not truly my own, I live as if they are. Because, from one automata to another, the world is better place if we do.

Leave a comment